Living in Southern California gives me an interesting perspective on transportation. Obviously, our public transportation sucks here: we over-rely on cars, live in over-sprawling metropolitan areas, spend too much of our lives in gas guzzling SUV’s driving over overcrowded freeways that cost us productivity as well as tax our mental health, and we manage to do all this while thinking of ourselves as the center of environmentalism.

But at the same time, because the state is full of people who care about the environment, it’s not like we don’t fund public transportation. Tax increases to fund bus and rail projects routinely pass, our major cities and metropolitan areas have all built light rail projects (and LA built a subway) with more in the pipeline, and, most famously, we passed a statewide bond measure to fund a high speed rail project between Los Angeles and San Francisco in 2008.

Um, about that high speed rail project….

I invite any reader to have a little fun reading the ballot arguments for high speed rail in 2008. We were going to sell $9.95 billion in bonds (that should have been an indicator that sponsors weren’t honest- anyone who uses the hoary old trick of pricing something at $9.95 rather than $10 is not on the up and up) for 800 miles of high speed rail track, stopping in San Diego, Los Angeles, Fresno, San Jose, San Francisco, and Sacramento, as well as communities in between, and also servicing Orange County, the Inland Empire, and the South Bay, and with a fare from Los Angeles to San Francisco of $50 a person for a 2 1/2 hour train ride. They promised the train would sell 70 million tickets a year, which works out to about 192,000 riders a day, or (assuming 700 passengers per train), 274 full trainloads of people riding every day.

Meanwhile the argument in opposition says that they were lying about the cost- instead of the $20 billion proponents were promising (they rounded up, of course, and assumed 1:1 federal matching funds), it would likely cost $90 billion, according to the opponents, which would make it “the most expensive railroad in history”. This is a rare situation where participants in a public debate understated their argument. In fact, the full cost of the train, according to the Los Angeles Times this past February, is now over $100 billion! Even the initiative’s opponents underestimated what a boondoggle this was!

The ballot arguments did not mention time of completion, but the original estimate was about 10 years. Meaning, we should have had our high speed rail up and running in 2019. It’s now 2021. Well, you might ask, don’t you at least have a partial train, maybe running between a few stations? Um… I hate to tell you this, but….

What we have is some concrete. It looks like this (photo credit: LA Times):

As you can probably tell, there’s no train tracks on those bridges. Indeed, the bridges aren’t even completed yet, which has to happen before any track is laid on them. I find it rather amusing that California’s large cadre of graffiti artists managed to complete their work on the bridge before the High Speed Rail Authority was able to complete any of its work on the project.

And, of course, this is in the part of the project where construction is actually taking place, in California’s Central Valley, far away from the big metropolitan areas of Los Angeles and San Francisco. As you can see in the photo, the area is flat and full of farmland- hardly a source of the hundreds of thousands of high speed rail passengers a day. The parts of the route that would connect Los Angeles to this bridge have been stuck in the planning stages for 12 years. San Francisco is in a bit better shape, but only because there was a preexisting plan to upgrade the “Caltrain” Peninsula Route that carries existing low speed diesel trains between San Francisco and San Jose; the same work would serve the high speed trains (if the project is ever completed), so you can at least say that some work is being done on that side of the project.

As many such projects do, the California high speed rail people have decided to open the project in stages- they think they can bring high speed service to some of the San Joaquin Valley communities such as Merced, Fresno, and Bakersfield in 2029, 21 years after the initiative passed. Such a train may draw a few riders (quite a few people ride the 6 trains each way per day existing Amtrak service up and down the San Joaquin Valley), but it would have to be heavily subsidized (San Joaquin Valley train passengers have a lot less money to spend than comparatively rich Los Angeles and San Francisco residents) and the raw numbers are far lower- rather than 192,000 riders a day, you might feel lucky if you got 1,000 more daily passengers atop the folks currently taking Amtrak.

You might think that I am going to try and impart a lesson about this, and indeed I am (besides “don’t believe cost estimates for major projects put forth by initiative sponsors”). And it is this- the fundamental problem with the California High Speed Rail project, the reason it was irresistible to voters, the reason why even now transportation enthusiasts who should know better act as if the thing is going to get completed and revolutionize American transportation- is what you might call the “Draw Lines on a Map” problem.

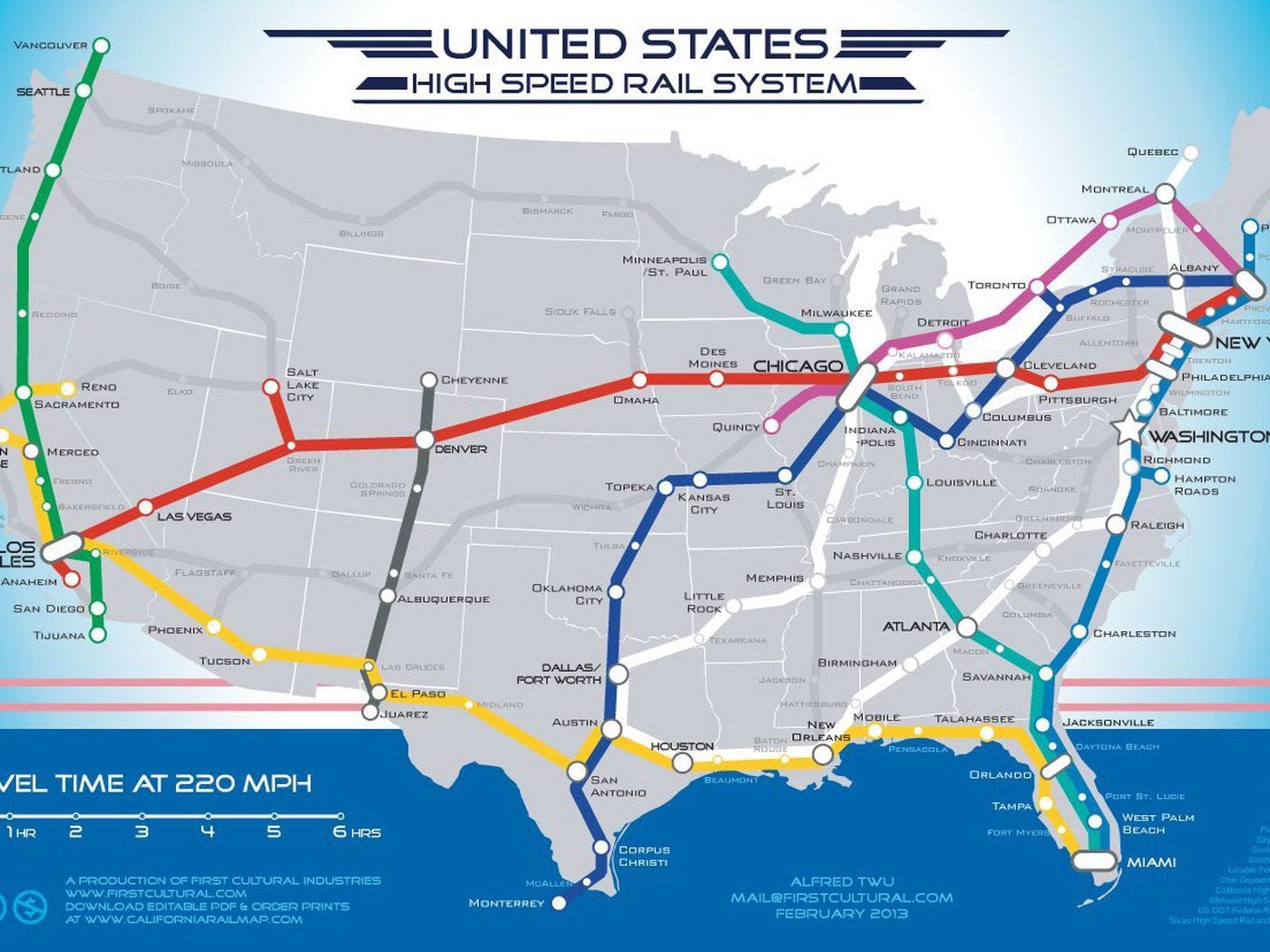

The Draw Lines on a Map problem works like this- it is really, really easy to look at a map of the United States (or California), identify obvious gaps in passenger railroad architecture, and draw lines. Recently, this map (image credit: Vox) made the rounds online:

This is the Draw Lines on the Map problem in its starkest form. This country is full of large metropolitan areas, seemingly at least fairly close together, with no or inadequate passenger rail service between them. By way of example only, you can see on the map that Houston and New Orleans are not that far away from each other. I’ve made the drive a few times- it’s about 5 1/2 hours. There’s an Amtrak train that serves that route- once a day, three times a week. And it’s often late because it runs on a long, important transcontinental freight railroad line, and the freight trains cause delays.

It’s perfectly understandable for anyone- especially anyone who likes trains or has ridden them in Europe or Asia- to look at that map and say “there ought to be a high speed train between Houston and New Orleans”. Indeed, it could even have a few intermediate stops- say Beaumont, TX, and Lafayette and Baton Rouge, LA. This is where the Draw Lines on the Map analysis stops.

But you will notice that in no way does that analysis actually prove that we should build high speed rail there. Indeed- and this is truly important- it doesn’t even tell you if you CAN build high speed rail there. Are there places where terrain would pose a problem because of hills, grades, or curves? (High speed rail can theoretically do somewhat better than regular rail on hills, but curves basically knock it out entirely- any change of direction at 180 miles per hour has to be incredibly gradual; that also rules out horseshoe curves and loop-the-loops, which low speed trains sometimes use to gain elevation on grades.) How many houses, privately owned farms, or businesses are you going to have to plow over to build it? (Remember, one of the advantages of high speed rail is it goes city center to city center, saving passengers a trip out to the airport. But that means you often have to build a bunch of grade separations and knock down some buildings in each urban area the train stops in.) What are the environmental laws that might slow up construction? Who are the local power brokers who could stop it?

And those are just the practical issues. There’s also a bunch of issues about cost (again, the more difficult the terrain, the higher the cost), projected ridership, subsidy (those $50 a passenger tickets require the government to foot a significant portion of the operating cost), etc. Drawing a Line on a Map is, simply put, not transportation planning. Indeed, it’s counterproductive to planning, because it makes things look easy.

And I should add, this isn’t solved just because the people Drawing Lines on the Map have more expertise. The California project is just a classic illustration of this. Here’s a brief history of intercity rail in Los Angeles- Los Angeles has five major intercity rail lines leaving the metropolitan area- the Coast Route, the Tehachapi Route, the Cajon Pass, the Sunset Route, and the San Diego Line.

The San Diego Line runs south, to San Diego, and is well served by passenger rail. Yes, it is slower than driving in no traffic would be (owing mostly to a winding course the railroad takes in La Jolla because of terrain, such as cliffs and canyons). But there’s always tons of traffic between LA and San Diego, and Amtrak is often in practice faster. The route supports a lot of daily trains. If it could be electrified and converted to higher speed, it might even support more trains and more passengers. But you can’t pass a ballot initiative on improving the San Diego Line alone- San Franciscans and Sacramento residents don’t care about it.

The Cajon Pass and Sunset Route run east and are part of two of the historic transcontinental railroads. Cajon Pass was the route of the famous Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe route between LA and Chicago, which might be called the Route 66 of rail travel. Before the jet age, a ride on the Santa Fe’s Super Chief was the luxury option for travel between Chicago (and by extension New York City) and Los Angeles. Nowadays, Cajon Pass is mostly a freight line for BNSF, the successor railroad to the Santa Fe, though Amtrak still runs a daily train.

The Sunset Route was the great transcontinental route of the old Southern Pacific Railway, running between Los Angeles and New Orleans, an old-time railroad hub. It is now operated by Union Pacific, SP’s successor, and also hosts a ton of freight traffic, as well as the aforementioned 3 day a week Amtrak service.

That leaves two routes going up to San Francisco. One, the Coast route, is double tracked the whole way and serves the communities of Route 101, mostly smaller cities like Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, and Salinas. Low speed trains take 12 hours to make their way from Los Angeles and San Francisco on that winding route, which includes a horseshoe curve that high speed trains could never negotiate. So that route doesn’t work for your high speed rail line.

That leaves Tehachapi. Tehachapi Pass and the small city of Tehachapi, in the mountains north of Los Angeles, feature a single through track which connects Bakersfield and Los Angeles. This is the only track connecting Los Angeles and Bakersfield, or Los Angeles and Fresno, or Los Angeles and Sacramento, and the only track other than the 2 slow Coast Route tracks connecting Los Angeles and San Francisco. Given the immense freight demand between Los Angeles and all these cities, you might wonder why there is only a single through track on the Tehachapi Pass. Well, that’s because it’s really difficult terrain.

The Southern Pacific built the Tehachapi Pass rail line in 1876. It was considered one of the greatest railroad engineering feats of the 19th Century. The direct route between Bakersfield and Los Angeles is now traversed by Interstate 5 and before that carried US Route 99- it goes up a windy, narrow canyon called the Grapevine, through the historic Tejon Ranch (owned by a very powerful private developer), at a 6 percent grade. It was impossible for Southern Pacific to build a train there. So they went east instead. They still had to go up into the mountains, but the grades were less steep and the canyons wider, giving them room to operate. Still, to get to the top, the SP engineers had to loop the single train track through a tunnel under itself (the “Tehachapi Loop”), as well as build several more tunnels to get to the top. It was expensive, but it worked. And Southern Pacific made a ton of money with the only train track between Los Angeles and the San Joaquin Valley.

This history is important because a second freight track between Los Angeles and Bakersfield (and thus a second option to avoid the slow Coast Route) would have been immensely lucrative for a railroad. Yet in 145 years, nobody has built one. It’s too expensive and too difficult.

And for high speed rail, things are even more difficult. High speed rail can’t go up the Grapevine- remember, steep hills are difficult, and switchbacks and curves are impossible. And high speed rail can’t do the Tehachapi loop either- again, you can’t do curves. So either way, you’d need a ton of tunnels. And… did I tell you about the earthquakes?

That’s right, the reason there is a Grapevine canyon and a Tehachapi Pass is because the entire mountain range was produced by uplift from the great San Andreas Fault, responsible for Southern California’s periodic (about once every 120 years) catastrophic earthquakes. (We are actually overdue for the next one.) And the Tehachapi mountains are one of the spots where the fault may produce one of those 8.5 magnitude tremors. What this means, practically, is that any tunneling is going to be prohibitively expensive, because the tunnel needs to survive a magnitude 8.5 quake a few miles away, maintaining its integrity in the midst of widespread landslides and earth movements in the vicinity. (It should be obvious that any design that would kill hundreds of people on a train due to a tunnel collapse caused by a foreseeable quake is a nonstarter.)

This, of course, is why construction in the Tehachapis hasn’t started and things remain “in the planning stages” 12 years after passage of the initiative. The actual cost of building high speed rail through the Tehachapi mountains, fortified to ensure no deaths even if a massive quake hits, is uncalculable. It’s certainly more than the bond or matching funds they have on hand, and there’s no point in committing to building something they could theoretically afford when once it gets into inevitable reviews and litigation, it will turn out to be insufficient to survive a foreseeable San Andreas temblor. Yet so, so many transportation experts continue to Draw that Line on that Map.

They have their responses, of course- how they have earthquakes in Japan and high speed rail seems to work there, or how tunnels have been built in Europe. All true, and none of which proves that it is practical to build anything in California. And- importantly- certainly nothing that proves you could build such a thing with a $9.95 billion bond initiative or that construction would take just ten years.

California politicians eventually recognized the scam, of course. Gavin Newsom is nobody’s idea of a budget tightening conservative, but when he saw what the realities were about constructing something that would actually go from Los Angeles to San Francisco, he canceled that part of the project. Instead, we are going to be left with some faster trains in the Central Valley that could, in theory, someday be connected to the two big metro areas. And, of course, to actually do that in the future will require solving the Tehachapi problem which nobody is really ever going to solve. Maybe we can put Elon Musk on it.

I kid, but of course, there’s nothing funny about any of this. The California voting public imagined that Line on a Map, and the sponsors of that initiative took quite a bit of their tax money based on the promise of that Line on the Map. Nobody told the public about the actual process, how hard it actually is to build something like this, or what the obstacles were in the Tehachapis. Indeed, they never even told the public that the construction would start by building something meaningless to help a few thousand people go to Merced, and even that would take two decades to complete. They took money out of people’s pockets that people would not have approved if they knew the truth. At the very least, any intelligent person knowing the truth would have made them prove how they were going to get over the Tehachapis first, and to build there first. That would have likely killed the project entirely, but if in some imaginary world they had been able to solve the Tehachapi problem, at least then the piece of infrastructure first laid down would have filled a real need, by creating the first passenger train tracks between Los Angeles and Bakersfield, and providing a connection to Los Angeles for those Amtrak trains running through the valley. That’s what you do if you actually take the conditions on the ground into account.

And that’s why Drawing Lines on the Map is such a bad way of doing transportation policy. The whole point of it is to hide all the difficulties, the practical realities, and the compromises necessary to actually construct a big transportation project. And as the California experience has proven, when you Draw Lines on the Map, people can actually get hurt, at least financially.

While I have no fondness for overly-rosy projections, the fact is that the challenges of getting across the Tehachapis were well understood, at least by those paying attention and indeed those developing the project. That section really should have been built early, but the EIS is approved now; just a matter of money. As with Switzerland's massively expensive and highly successful rail tunnel program.

The cost overruns so far are largely due to a crooked contractor; lack of expertise in-house meant that Tutor Perini scammed the HSR Authority on the first contract; they wised up and hired better contractors for the later contracts. Lack of in-house expertise and being scammed by contractors is a recurring problem in US passenger rail construction. Which has nothing to do with people who draw lines on maps.

And I'll warn you: Ralph Vartabedian at the LA Times is not an honest reporter, and deliberately misleads about a lot of stuff, including numbers. Normally costs are quoted in "current year" dollars; a ridiculous amount of the supposed increase in price is due to a shady change where they're being quoted in "estimated year of expenditure dollars based on estimated future inflation", which is basically just a way of making the costs look larger. Vartabedian doesn't mention this, because of *course* he doesn't; his articles have been consistently misleading. They're misleading on a lot of other points too.

And perhaps that is the biggest reason we don't build high-speed rail in this country; it's the only country with an active anti-rail disinformation campaign.

Dilan, thank you for the insightful writing. Musk cited his dislike for the superlatives attached to the San Francisco to LA line (slowest, most expensive per mile high speed line) as his reason for bringing about hyperloop. Where would Hyperloop fit in this discussion?