The Supreme Court Needs To Stop Wasting Its Time And Hear More Cases Instead

A different critique of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is under fire this week. Understandably so, because it just announced that Presidents have immunity from many criminal prosecutions, a decision that not only seems bad as a matter of policy (it encourages Nixon-like behavior from Chief Executives) but also as a matter of constitutional law (while there are some islands of exclusive presidential power in the Constitution like the pardon and the veto, Presidents normally take direction from Congress and it’s crazy to think that Congress cannot use criminal statutes to constrain presidential excesses). And of course, you can argue that the Supreme Court is on a run of unpopularity dating back to the Merrick Garland imbroglio, where Mitch McConnell refused to hold hearings on Garland’s nomination and kept the seat open for Donald Trump to eventually fill it with Justice Gorsuch. There was also the Dobbs decision a couple of years back, in which the Court overturned the popular Roe v. Wade precedent protecting abortion rights.

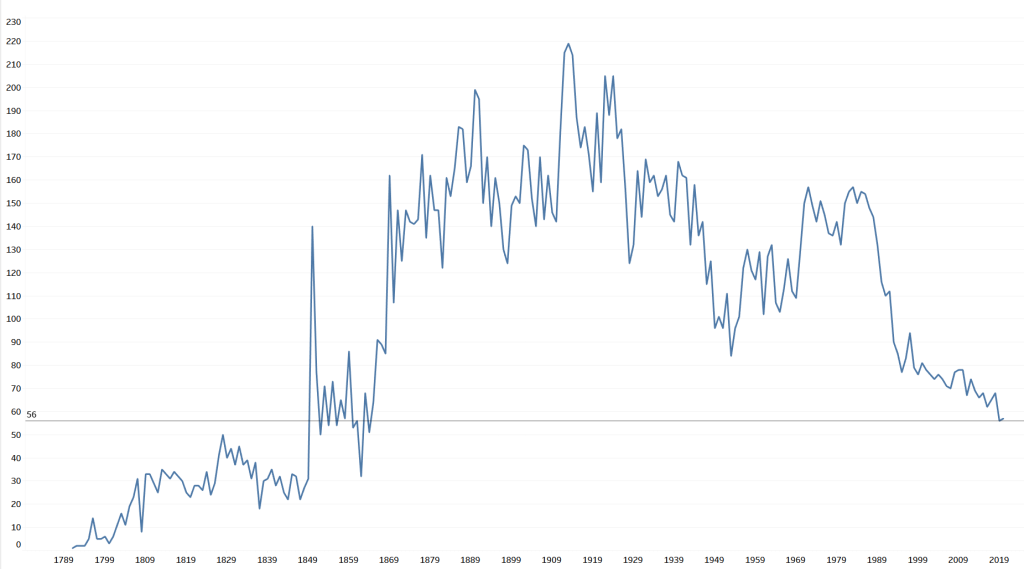

But while there’s a vigorous debate about the Supreme Court’s ideology going on, there’s something else that the Court is doing that gets less attention— the Court is taking far less cases than it once did. You can see it in this graph prepared by Reason magazine:

Since the mid 1980’s the Supreme Court’s caseload has been cut in half. Why does this matter, you might ask? Especially a liberal might ask that, given it doesn’t seem readily apparent why one would want a conservative court to decide more cases. But here’s the thing: they still do decide the big politically salient cases that make you cringe with their 6-3 outcomes. Indeed, they probably take more of those than they used to, especially when you count cases on the so-called “shadow docket”, the usually lightly briefed and unargued cases where the Court decides whether to stay lower court decisions or issue injunctions that bind the nation. What they don’t do is decide the cases that they are supposed to— the circuit splits.

As someone who has written petitions for Supreme Court review and oppositions to petitions for Supreme Court review, I can tell you that traditionally the main criterion for when the Court takes cases is to resolve a conflict between two important lower courts. Most often, it is two “circuit courts of appeal”, the intermediate level federal court. Less often, but still not uncommon, it is to resolve a split between a federal court and a state supreme court, or two state supreme courts. But the notion is simple and obvious— at least two important lower courts have decided the same issue of federal law, and one decided it one way and the other decided it the other way. To take an obscure issue from early in my legal career, there is a statute called 28 United States Code Section 1350, which allows noncitizens to sue in federal court for certain international law violations. The different circuits had made inconsistent decisions as to which international law violations were covered by the statute and which were not. Eventually, after this went on for a time, the Supreme Court stepped in and took the case I was working on, Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, and clarified the matter.

I didn’t much like the result of Sosa, but I have no qualms with the process. The issue was important, as there were lots of Section 1350 suits being filed. And having a different legal standard apply in one region than in another is unfair to those who are forced to litigate in a particular region (often, all defendants and some plaintiffs) and encourages “forum shopping” where plaintiffs have a choice as to where they bring the suit under jurisdiction and venue rules. The Supreme Court has to come and impose uniformity. That is, truly, the most important job of the Court.

Now, to be fair, the Court has never denied that it also steps in to decide cases it sees as having national importance. And many of these cases are the politically salient ones everyone now debates online— the cases involving hot button political issues, like abortion or gun control, or key parts of the presidential agenda, like student loans or immigration policy, or politicians themselves, such as the Trump immunity case just decided.

The key to understanding the problem is this: the Court is always going to take a certain number of politically salient cases, because it sees them as having “national importance” and, frankly, because the justices are human beings and want to work on interesting cases they care about; the problem is that what we actually need the Court to do is resolve circuit splits, which is usually less exciting work.

But, you might ask, “why not both?”, as the old Twitter meme says.

Well, the problem is that the Court has limited bandwidth. It’s only nine people and they have to decide all the cases themselves. Lower courts divide themselves into three judge panels and only take the most important cases or the cases that split the judges en banc, or as a full court. But in the Supreme Court, other than with respect to a few “shadow docket” matters, the entire court hears every case.

But why, then, is the number of cases the Court is working on declining. I have a theory. The number of cases is declining because as the Court has become more politically salient, the justices enjoy that role and commit a lot more time than they need to into deciding the politically salient cases.

I can already see the objection to that. Don’t we want them spending lots of time on cases, especially important ones. And of course, if they need to take the time to decide a case correctly, of course we want them to take that time. But that’s not what’s happening. The politically salient cases are the most likely to be decided 6-3 on ideological lines. This means, in most cases, the Court makes up its mind quickly in these cases. (The Court is much more likely to decide cases unanimously or across ideological lines when the cases have less political significance.) This term, some of the 6-3 liberal-conservative decisions included the decision invalidating the “bump stock” regulation, a mild form of gun control that banned the accessory that allowed the Las Vegas shooter to spray his victims with bullets, the decision holding that courts would no longer defer to the interpretations of statutes by Biden’s administrative agencies, and, of course, Donald Trump’s immunity claim. If you think any of those decisions required a great deal of deliberation and thought by the justices, you are wrong. They came in with their partisan minds made up.

And yet, those cases weren’t decided until the very end of the Supreme Court term. Why? Because of the real reason the Supreme Court takes so few cases now— because they wrote, and wrote, and wrote.

A lot of folks who write about the Supreme Court tend to be transparency nerds. You know the type— the sort of person who is outraged that a government agency is doing something behind closed doors or with few people watching. And as a result, I think they are biased towards all this writing. Indeed, it has become de rigueur to demand more writing from the Court, particularly on shadow docket matters. Indeed, there are even Supreme Court nerds demanding that opinion announcements, a meaningless piece of ceremony that has no impact on what the law is, be broadcast to the world.

I’m here to tell you the truth is the opposite. The Court needs to write less. Let’s trace the history. Originally, the Court had six justices, and every justice wrote on every case. This is the way British courts did it, and it was called deciding a case seriatim. The parties and the lower courts would then tally up the votes and determine what the Court meant. Pretty quickly, it turned out the Court did not like that, both because it forced every Justice to write in every case (work!) and because you had trouble figuring out exactly what the Court had held with all those opinions. So Chief Justice John Marshall, the third Chief Justice, who is generally considered the father of the modern Supreme Court, changed the practice. Instead, a single Justice would speak for the Court. There would be one opinion and lower courts would know exactly what the Court held. This worked, and also spawned another tradition— the separate, concurring or dissenting opinion. These opinions would note someone’s disagreements with the majority’s decision.

The key point about early concurring and dissenting opinions is they tended to be short. For instance, Cooley v. Board of Wardens was a famous early interstate commerce clause case dealing with the scope of federal powers. It drew two dissents- a four page dissent from Justice McLean and a two page dissent from Justice Daniel. Or take the famous Amistad case, which inspired a Steven Spielberg movie: there was a dissent in that case, which was a page long.

Indeed, sometimes Justices dissented without an opinion at all. Buck v. Bell, an infamous early 20th Century case approving eugenic sterilization, drew a single dissent from Justice Butler— it was one line long, noting that he dissented.

But what about the “great dissenters”, you might ask— the famous thundering dissenting opinions that were later adopted as majority opinions by the Court and which were vindicated in the court of history. Well, some of them were longer— Justice Harlan’s justly famous dissent against legalized segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson was ten pages long, and Justice Brandeis’ attack on warentless wiretapping in Olmstead v. United States went fifteen pages. But Justice Brandeis’ concurrence in Whitney v. California, which help give rise to modern free speech law, was only 5 pages long. Justice Holmes’ dissent in the “freedom of contract” case, Lochner v. New York, was just 2 pages, perhaps the most famous 2 pages in the history of the Court. Justice Jackson’s indictment of Japanese internment in Korematsu v. United States? Just six pages.

Nowadays, it’s very different. Take United States v. Rahimi, the recently decided case holding that domestic violence offenders can be temporarily barred from possessing guns. It wasn’t even a very controversial case— the vote was 8 to 1. But after an 18 page majority opinion, the case features eighty-one pages of concurrences and dissents. That’s right, the Court wrote almost 100 pages total on a case whose result was so obvious that all but one of the justices agreed on it. Or take the Trump immunity case— counting separate opinions, the justices wrote one hundred and eleven pages, of which 68 pages were concurring and dissenting opinions. This is not unusual. This is standard in these big, famous cases. Everyone wants to write, and they want to write a lot.

And the thing you have to understand is that this is especially egregious with the concurrences and the dissents. Concurrences and dissents are not law. Very occasionally a concurrence will help you find out what the law is, by pointing out that the votes don’t exist for something that otherwise might be implied in the majority opinion. For instance, Justice Kavanaugh, concurring in Dobbs, signaled that the right to travel would apply to traveling to get an abortion, and that the Court would not overturn gay rights and contraceptive cases. He was the fifth vote and that was useful information! But that is rare. Most concurrences and dissents tell you nothing about the law. They are just justices popping off and wanting to get their 2 cents in on the big political issues.

And remember, this is exactly what Chief Justice Marshall tried to get away from when he ended seriatim opinions. The Court should speak with one voice, so that litigants and lower courts could listen. Now, everyone’s speaking, but for no reason— all those concurrences and dissents are not law.

But, you might ask, isn’t there a tradition of a “great dissenter” who persuades future courts even if the current court ignores him? And, sure, there is, but I listed some of those great dissents above. They were short. Indeed, brevity is a big part of persuasion— people don’t like to read long-winded prose.

In addition, it is, at the very least, questionable that all these dissents, or even a good number of them, are really going to become majority opinions in the future. And for this, we have to talk about Justice Clarence Thomas. Nobody likes writing separate, lone wolf opinions more than Justice Thomas. And, not to put a fine point on it, far from persuading the next generation, many of the positions he takes are dangerous, extremist, have little to do with the law, and are unworkable and frankly nuts. Here are some of the opinions Justice Thomas has expressed in long lone wolf dissents:

That high school students have no constitutional rights whatsoever.

That Americans have no constitutional right to purchase birth control.

That Congress has no power to ban products made with child labor from the interstate marketplace.

That there are no limits on presidential power in wartime, including even those imposed by congressional statute.

Indeed, the Trump immunity case contains a typical lone wolf Thomas concurrence. He is obsessed with the fact that the special prosecutor who was appointed by the DOJ to prosecute Trump is a private citizen and not an attorney within the department. He thinks that is unconstitutional. Not a single other Justice joined him, even stalwart conservatives like Justices Alito and Gorsuch. It’s crazy. But Thomas wrote 9 pages on it. He does this all the time.

Indeed, he even does this all the time in cases the Court doesn’t even agree to hear. The “dissental”, the dissent from denial of certiorari, has become more common and has become another opportunity for the Justices to do something other than deciding cases on issues that split the circuits. And Thomas is the king of the dissental. Just today, he wrote that OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a key agency that protects the health and safety of the American worker, is unconstitutional. This is just pure extremism— Justice Thomas is saying he’s willing to kill American workers just to be purist about an obscure doctrine, the nondelegation doctrine, that was used in a couple of cases back in the 1930’s. Now thankfully, Thomas’ dissent is just three pages— but he isn’t the only offender on dissentals. In fact, just today, the Court issued 44 pages of dissentals— including dissentals from liberal lions such as Jackson and Sotomayor as well as Thomas’ screeds.

And all this is made worse by the Court’s fetish for originalism. The Court routinely digs into 18th and 19th Century materials, sending its clerks on wild goose chases to obtain the most obscure sources to cite in its opinions and tout its originalist bona fides.

So what we have is a court that is writing way too much in separate opinions— concurrences, dissents, and dissentals— which are not law. Meanwhile, the amount of law they actually produce is steadily decreasing. See the problem?

This needs to stop. And I am afraid the people who regularly write about the Court are part of the problem. Again, they like content and like transparency. But for the Court to have more bandwidth, it needs to produce less content. Everyone should not be writing a separate opinion in a case like Rahimi. The goal should be one majority opinion, and one dissent, with the dissent being short. If Justice Brandeis could do it in 15 pages, so could these guys. Justice Thomas should simply knock it off- if he wants to write pieces about how the law is all wrong, he should do it during his summer vacation time and not when the public is paying him to decide cases, and he should publish his work product in conservative journals, not in the United States Reports. And everyone should stop writing dissentals. If cert is denied, cert is denied. We don’t need a long explanation.

If the Court enacted these reforms, it would free up more bandwidth to take more cases and winnow down on some of the many circuit splits that have festered for years. We’d have a court that is more useful to the American public, rather than one that is more performative. And isn’t that what we want a court to be?

Terrific essay, and thought-provoking, but just because you don't agree with his opinions doesn't make them "dangerous, extremist, have little to do with the law ... unworkable and frankly nuts." Thomas has a vision of the country closer to the founders' vision, and he bases his opinions on that vision, essentially requiring continued democratic assent to wholesale expanses of government power. He is arguably the most influential member of the court, since his ideas have gradually come to dominate the largest block on the bench, and some of his "crazy," federalist ideas are now the law of the land. A lot of people say he's the most likeable guy on the bench, too. Belittle him at your peril.

Two pages might take longer to write than ten!